Introductory note: The following is an edited presentation I made on February 5 to Congregation Beth Torah, a Reform synagogue in Ventura, California.

The trauma of October 7th remains palpable in Israel and for so many of us in the Jewish Diaspora despite the official end of the war in Gaza, though fighting continues there and there’s growing violence in the West Bank. Israeli society is struggling to absorb the horrors of that deadliest and most traumatic day for Jews since the founding of the State of Israel and the Holocaust. Border communities still bear the scars of destruction and displacement. The trauma of war affects virtually every Israeli. To have seen the starving and tortured faces of some hostages as they were released recalled the old black and white photographs taken when the camps were liberated in 1945.

Israelis now find themselves at a crossroad in their history, and so too do we American Jews. For the first time in American Jewish history since the founding of Israel, many liberal American Jews are shaken not only by what happened on October 7 and being blamed by anti-Israeli antisemites for the attack starting on October 8, but by Israel’s overwhelming military response against Hamas that killed tens of thousands of Hamas terrorists and tens of thousands of innocent Palestinian civilians.

American Jews must understand that this longest war in Israel’s history was a legitimate response to Hamas’ butchery of Israelis in the south and what the Israeli government and the IDF most feared might happen immediately after October 7, that they were fighting for the existence of the state itself. They knew Hamas intended to expand its attack and cruelty, that there were realistic threats as well by Hezbollah and Iran to join the war, and that a sympathetic uprising could ignite in the West Bank forcing Israel to fight simultaneously on three fronts. It was unclear whether Israel could meet those threats.

The IDF was disorganized and its command believed it had to distribute its authority to a far lower level of officers than it had ever done before, a decision that reduced the IDF’s customary safeguards to protect Palestinian civilians who were being used by Hamas as human shields. They believed that Israel had to fight with overwhelming fire power to disrupt Hamas’s chain of command and reach its leaders hiding everywhere in more than 400 miles of tunnels everywhere under homes, apartment buildings, schools, community centers, hospitals, and mosques. If Israel didn’t succeed in disrupting Hamas immediately and demonstrating to Hezbollah and Iran how capable the IDF still was, Israel’s leadership feared that tens of thousands of Israelis could be killed.

Both Israelis and American Jews are only now beginning to ask about the impact this war has had on Israelis and Palestinian civilians and what long-term psychological damage has been done to both peoples. We’re trying here in Diaspora communities as well to figure out where we stand as American Jews and how much we want to say publicly about our fears and moral concerns in relationship to the war, the illiberal social and ethical trends that have grown in Israel, and the growth of antisemitism on the far right and far left.

Taking a 10,000-foot view, the significance of this period in Jewish history is unparalleled in the modern era except for the three years from 1945 to 1948 when the Jewish people went from our lowest nadir after the Shoah to the establishment of the Jewish State. That wide swing of the pendulum is testimony to the Jewish people’s durability and ability to survive, adapt and thrive after catastrophic events.

It will take time for Israelis, most especially, to heal from the losses and trauma of the war. Whatever happens, however, there must include a pathway to a demilitarized Palestinian state of some kind in Gaza and the West Bank in the context of a larger Middle East peace agreement that includes Israel and Saudi Arabia and all of Israel’s moderate Arab neighbors. The vast majority of Israelis, however, are no longer speaking about the viability of a Palestinian state. They fear, legitimately, that any such state could well be taken over by Islamic extremists bent on Israel’s destruction.

The war, in part, solidified for now the hold that right-wing Israeli political parties and the extremist settler movement have on Israeli politics. Should those extremist and messianic forces have their way in the next Israeli election in October, more terrorism and war with the Palestinians and Islamic extremists will be inevitable and Israel’s democracy will be threatened.

Israelis are facing many significant challenges including what to do about the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, the lack of a consensus about the role of the Palestinian Authority in the future governance of Gaza and the West Bank, Israel’s severely damaged international standing, what we in the American Jewish community think and feel about Israel and Zionism, and the dramatic rise in antisemitism around the world.

Among the greatest and immediate internal challenges facing Israel is that it has yet to set up an objective state commission of inquiry into what happened leading up to October 7 and Israel’s conduct in the war. Israel needs a power-house independent authority to undertake this inquiry to restore the people’s confidence that every lesson has been learned, that leadership failings are exposed, conclusions are drawn, and whether military excesses and war crimes were committed.

In considering Israel’s culpability, we Jews in the Diaspora who love Israel have to be able to distinguish between two kinds of criticism leveled against Israel’s conduct of the war. There’s criticism from Israel’s friends that the IDF went too far, bombed Gaza too heavily, and that Israeli commanders and soldiers, in the heat of battle, crossed red lines against international moral and legal standards of war. Israelis and right wing American Jews need to address this legitimate criticism from Israel’s friends and not characterize it either as anti-Israeli or antisemitic.

The second kind of criticism comes from those who believe that the Jewish State has no moral legitimacy to exist, that it is a colonial and foreign entity in the heart of the Islamic Middle East, and no right to defend itself. That criticism is not only anti-Zionist and anti-Israel, but is antisemitic because it denies to the Jewish people what is the right of every people in the world, to define ourselves and our narrative, and to have a nation state in our historic Homeland.

Despite the loss of a thousand young Israeli soldiers in the war, the murder and suffering of surviving hostages and their families, and the massive carnage and loss of life and property in Gaza, there are a few positive things for Israel and the Jewish people that have come from this war.

Immediately after October 7, Israel’s civil society came together from across all political and religious lines to support one another. In Diaspora communities $1.4 billion was raised for Israel representing the single largest set of contributions on behalf of Israel in our history, and 300,000 Jews and friends of Israel convened in Washington, D.C. in solidarity with Israel, the largest Jewish demonstration since the 1987 Soviet Jewry rally on the Mall.

Many American Jews felt a reconnection to Zionism, Israel, and their Jewish identity. More than 70% of Jewish Diaspora adults feel emotionally attached to Israel, and 60% said Israel make them proud to be Jewish. 70% said that it is sometimes hard to support actions taken by Israel or its government. 74% of American Jews between 18-49 support self-determination for both Israelis and the Palestinians, and 88% believe that “Israel has the right to exist as a Jewish, democratic state.” But, 14% of Jews ages 18 to 34 identify as anti-Zionist, an increase from 8% five years ago.

In the early weeks and months of the war, many American Jews sought out the organized Jewish community for identification and support, began reading books about Israel, attending classes and on-line seminars on Zionism, Israel, Middle East history and politics. Non-Jews chose to convert to Judaism in numbers greater than we’ve experienced in a generation.

However, too many American synagogues have become unsafe spaces where rabbis and congregants are unable to discuss civilly the wide range of views concerning Israel, Zionism, antisemitism, the war, the Israeli government, illiberal trends in Israeli and American Jewish communities, and the Israeli-Palestinian and Israeli-Arab conflicts.

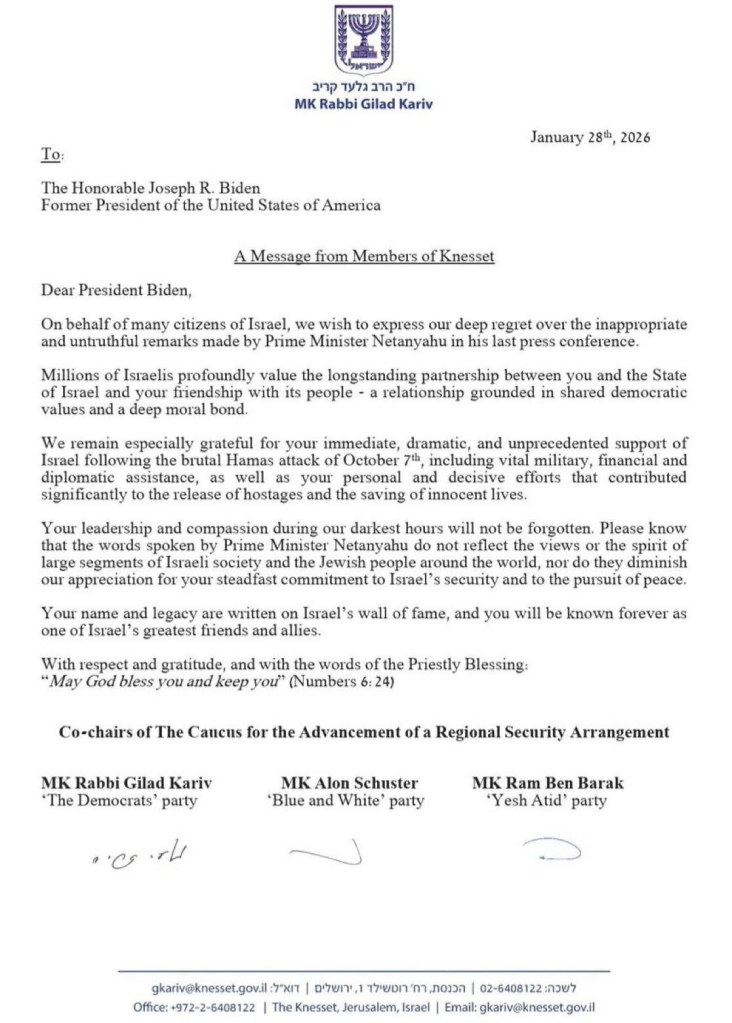

It ought to be clear to everyone that we North American Jews and Israelis are in a significant transformative era. Whereas in years past, Israelis were happy simply to take Diaspora Jewish dollars and welcome American Jewish political support in Congress and the administration for Israel’s security needs. In a recent Israeli poll, 80 percent of Israeli Jews now feel strongly that the Israel-Diaspora relationship is important to them personally.

Though we Jews are one people, there exists today a wide chasm between most Israelis and most liberal American Jews. That reality requires us American Jews to understand that since October 7, Israelis as a whole have thought of themselves, perhaps for the first time in their lives, as victims who responded to Hamas from a place of fear, anxiety, rage, hostility, and a desire for revenge. From that embattled position many Israelis have justified themselves morally in responding militarily in Gaza to whatever the Israeli government and the IDF did. In the initial months of the war, I felt as Israelis felt. Feeling victimized perhaps explains why the vast majority of the Israeli media did not focus throughout the war on the destruction of Gaza and the huge loss of life there, and why Palestinian society has historically tolerated and embraced terrorism as a legitimate response against Israel and the Jewish people.

Consequently, Israel has lost the affections of a small minority of the American Jewish community, especially among our young people. At the beginning of the war, a colleague called me distraught because his college-age son had joined the Jewish Voice for Peace, an anti-Israel and anti-Zionist Jewish organization. His son claimed to want no part of Israel in his life and even said that Israel should never have been created. My colleague was deeply upset and asked me what I thought he ought to say to his young adult son. A number of my congregants called me as well with the same question about their college age and twenty-something sons and daughters.

I responded this way:

“First – these are your kids. Your relationship with them is what’s most important now. Don’t say or do anything to alienate them from you. Love them a lot, which means listening to them without having to instruct or correct them. Recognize that we’re all struggling in this new era of American Jewish history. Remember that they’re at the beginning of their adult journeys as Jews and they likely will evolve and change their thinking just as we’ve done over the course of our lives. You’ve instilled in them liberal Jewish values focused upon justice, compassion, and peace. This is not the end of their engagement with Jewish life or in their relationship with Israel. They already know how you feel and what you believe about Israel. If they’re open to reading about why Israel matters to the American Jewish community, to our identity and security in the Diaspora, and what liberal Reform Zionism has to offer them, there are books that deal directly with these challenges.”

The greater question confronting us now is how to better educate ourselves and our young people about Israel and Zionism. The best thing is to go there and meet Israelis face to face from the right, left, and center, with Palestinian-Israeli citizens and Palestinian Arabs living under occupation in the West Bank, with Israeli and Palestinian journalists, members of the Knesset, and our Israeli Reform movement rabbis and leadership, including the leadership of the Israel Religious Action Center, the social justice arm of Israel’s Reform movement, who advocate daily before the Knesset and courts and in the media on behalf of pluralism, equality, inclusion, and democracy in Israeli society.

There are many questions all Diaspora Jews, young and senior alike, need now to be asking:

- What does it means for us to belong to the Jewish people and have a Jewish state?

- How ought we to respond to those who feel we Jews are colonialists and interlopers in our historic Homeland?

- How do we rebuild trust in our Jewish institutions, clergy and teachers who many young people regard with suspicion and distrust because we haven’t been honest enough about Israel and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict when they grew up?

- How do we understand anti-Zionism, anti-Israel sentiment and antisemitism today?

Our message as American liberal Zionists and lovers of the people and State of Israel has to be clear and unrelenting – DON’T GIVE UP ON ISRAEL. We have a moral and Jewish duty to fight for Israel despite her imperfections just as we have a moral duty to fight for American democracy despite its obvious imperfections.

As Reform Jews, we have the duty also to join with our growing Israeli Reform movement in its fight for religious pluralism, democracy, inclusion, and equality in the Jewish state, and to pursue with those Israelis who believe in the necessity of creating a new pathway to peace with the Palestinians, the Arab and moderate Muslim world.

My Zionism grew from a particular time in history. I was born a year after the State was established and was raised on “the crisis narrative” of Jewish history. The Holocaust hovered over my childhood and formative years and has been a defining experience affecting the post-war Jewish psyche. The Shoah taught Jews everywhere that powerlessness risks death and the State of Israel is our surest protection against deadly forces that would destroy us.

By the time I was 17, Israel had fought three wars. When I was 23 and living in Jerusalem, Israel was nearly overtaken by Egyptian and Syrian forces in the Yom Kippur War. I understood then that Israel could not lose a single war on the battlefield, that her security and survival must be the number one priority for Israelis and world Jewry, and that to ignore the real threats to the Jewish people can never be an option.

Though I grew up with the “crisis narrative” of contemporary and historic Jewish experience, that narrative is no longer sustainable despite what happened on October 7.

I agree with Dr. Tal Becker, an associate at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and a Fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, who writes that the crisis narrative “is both narrow and shallow.” It’s narrow because the singular focus on survival keeps us from talking about “the breadth of what this sovereign project [on the land] might offer for the collective Jewish experience.” And it’s shallow because “it pursues Jewish survival for its own sake but tells no deeper story as to why that survival is important and worth fighting for.”

Dr. Becker argues that to achieve a vision of Jewish unity behind an Israel that we can support, we need to focus on values and ask what it will take to address Israel’s challenges and build a moral and just society in which the policies, politics, and culture reflect our liberal Jewish values, tradition, and experience as a people.

For those operating strictly out of the crisis mindset, Jewish unity is defined narrowly by who stands with us against common threats. But the values narrative defines Jewish unity in terms of a moral engagement that we share – not because we agree or because the one overriding issue confronting us is survival, but because we’re committed to engage in a process of writing together the next chapter of Jewish history.

It’s difficult to find the balance between our particular Jewish interests—the concerns and identity we have as a nation and “tribe”—and our concerns for democracy and the wellbeing of all. Yet the tension between the particular and the universal, the tribal and the humanitarian, runs throughout Jewish tradition and history. A values-based discussion about what Israel should be can bring about a new Zionist paradigm.

“Aspirational Zionism” evokes these questions that can take us to the heart of a democratic nationalism:

How do our liberal Jewish values augment Israel’s democratic, diverse, and pluralistic society?

How do we bring the moral aspirations of Judaism into contemporary challenges like Israel’s relationship with the Palestinians and Arab-Israeli citizens?

How do we fight our anti-Israeli, anti-Zionist, and antisemitic enemies without our sacrificing our Jewish moral sensibilities and democratic values?

How do we genuinely pursue peace as a moral obligation despite the threat of terror and war?

How do we preserve a Jewish majority in Israel while supporting social justice, a shared society with Arab-Israeli citizens, and the human rights of all?

Nationalism has become shorthand for self-interested exclusion, oppression, and supremacy, but democratic nations are what we make them. In this spirit we can insist on and fight for an Israel that lives up to its founding principles of democracy, justice, and peace; an Israel that reflects the best of Jewish culture and tradition.

We liberal American Jews can be fully Zionist even as we ask the hard questions like those above. That’s the Israel and the Zionism I support and grew up with, and our support for our Reform Zionist movement in the United States and in Israel in our Israeli Reform movement’s synagogues, youth programs, pre-army educational programs, kibbutzim, and social justice work are what give me hope for Israel and the Jewish people.